Chang'e-7: Hunting for Lunar Water Ice in Permanent Shadow Zones

When China’s Chang’e-7 mission launched aboard a Long March 5 rocket in August 2025, it began a historic quest to unlock one of the moon’s most guarded secrets: water ice hidden in the permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) of the lunar south pole. These craters, untouched by sunlight for billions of years and colder than Pluto’s surface, are believed to hold frozen water that could revolutionize deep space exploration. Equipped with cutting-edge robotics and international scientific instruments, Chang’e-7 is not just searching for ice—it’s paving the way for sustainable lunar bases and reshaping global collaboration in space.

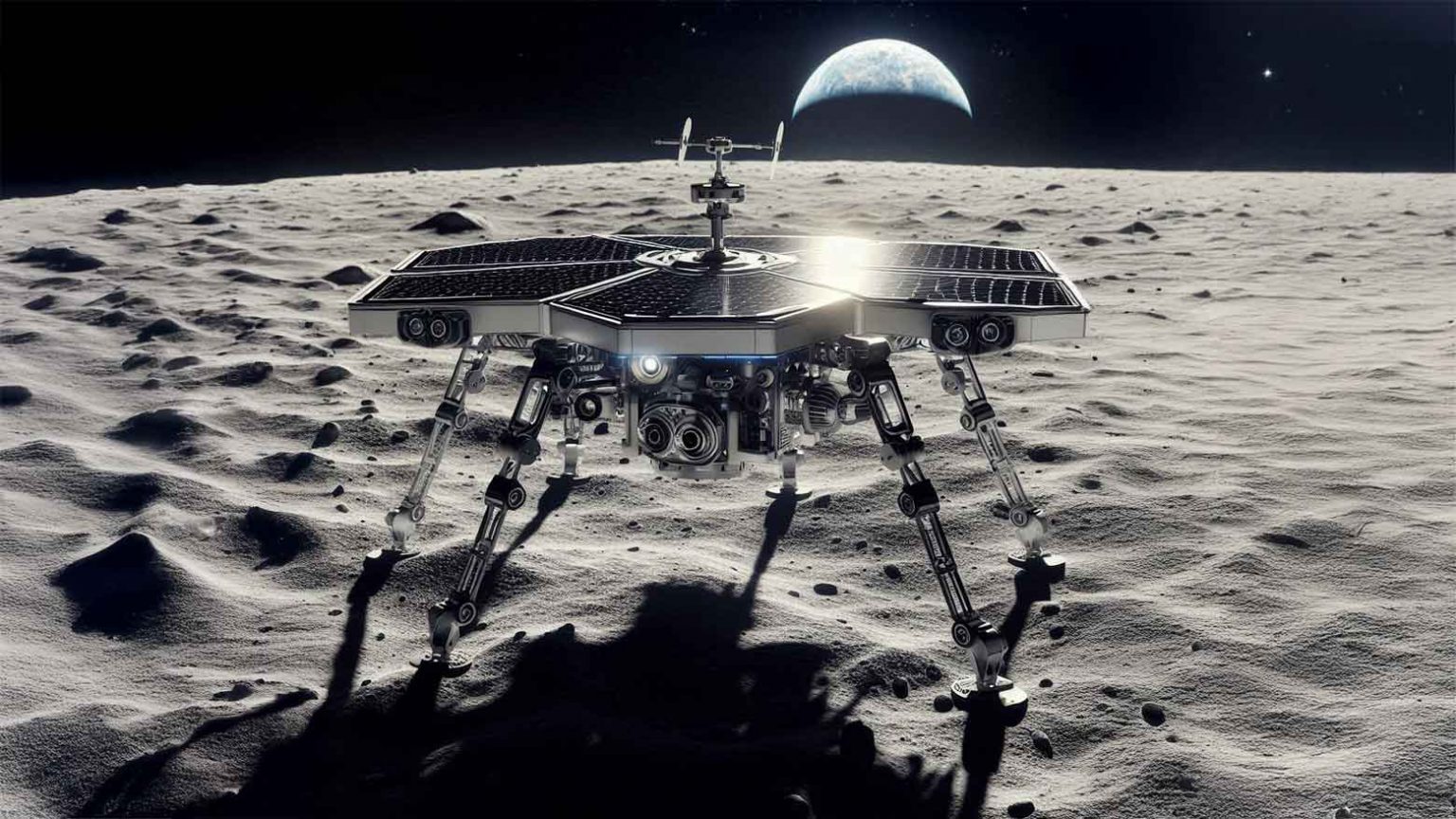

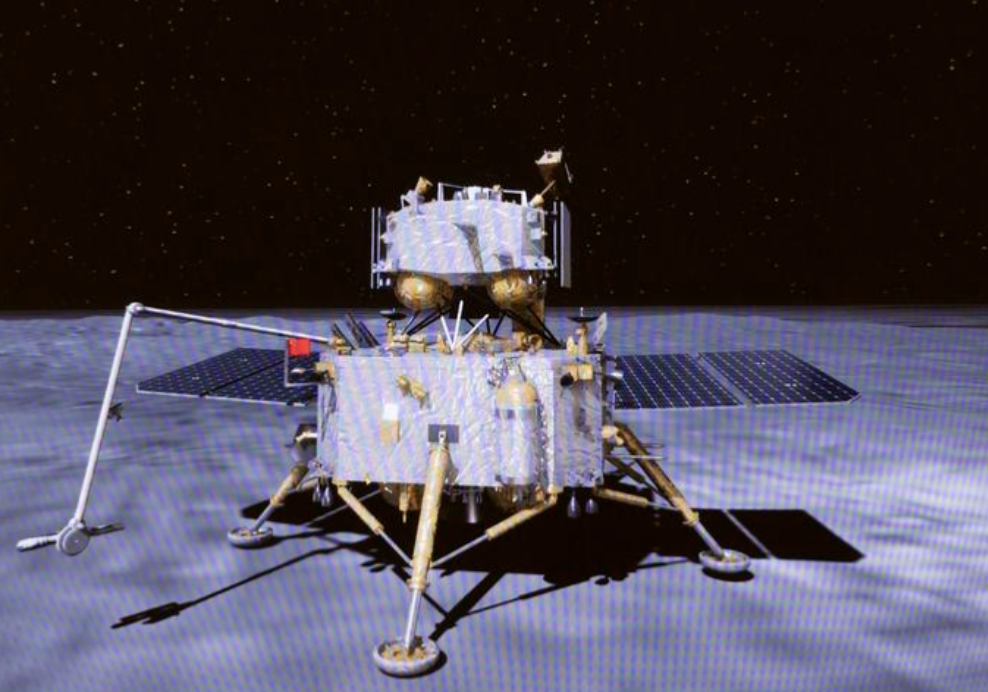

At the mission’s core is a technological marvel: a six-legged flying probe capable of crawling, jumping, and soaring across the moon’s rugged terrain using rocket propulsion. Unlike traditional rovers limited by wheeled mobility, this agile explorer can leap dozens of kilometers to reach PSRs like those within Shackleton Crater, where temperatures plummet to minus 230 degrees Celsius. Its suite of instruments includes a lunar soil water molecule analyzer, which will directly sample regolith to confirm ice presence and concentration—a critical advancement after ground-based radar studies suggested ice exists in patchy deposits up to six weight percent in some areas . Supporting this probe is an orbiter with microwave imaging radar and a lander carrying seismometers, working in tandem to map subsurface ice and assess lunar quake risks for future bases .

International collaboration defines Chang’e-7’s scientific approach. Six countries and one international organization contributed payloads, including a hyperspectral camera developed jointly by Egypt and Bahrain to analyze surface minerals from orbit . Switzerland provided a magnetometer, while Italy contributed to radiation monitoring—creating a global dataset that will benefit all lunar exploration efforts, including NASA’s Artemis program. This cooperation mirrors the mission’s goal of democratizing space resources; water ice, once extracted, could be split into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel or life support, reducing reliance on Earth supplies that cost millions of United States dollars to transport .

The mission’s target, Shackleton Crater’s sunlit rim, offers strategic advantages: near-perpetual solar power for operations while keeping PSRs within reach. This location, also eyed by NASA for Artemis landings, highlights the south pole’s importance as a hub for 21st-century lunar exploration . Chang’e-7’s data will help answer key questions: How did water form in these frigid wastelands? Is it distributed densely enough for practical use? Early results from its 18 scientific instruments, including a ground-penetrating radar and Raman spectrometer, could resolve debates about lunar water’s origins—whether delivered by comets or formed in situ by solar wind interactions .

As Chang’e-7 begins its 14-day journey to the moon, its success could redefine humanity’s relationship with space. By demonstrating access to extraterrestrial resources, it moves the dream of sustainable lunar habitation closer to reality. For scientists, engineers, and space enthusiasts worldwide, this mission represents more than a technological feat—it’s a step toward a future where the moon serves as a gateway to deeper space, with resources shared for the benefit of all nations. In the silent darkness of lunar PSRs, Chang’e-7 may just illuminate the path to humanity’s next giant leap.

(Writer:Tommy)